How the Microvision Inspired Nintendo’s Game and Watch

March 27, 2021I’ve never really believed the old story that the Game & Watch was inspired by a man playing around with a calculator on a bullet train.

And it turns out it wasn’t, at least not really.

The original story — one repeated ad nauseam by newspapers, gaming sites, even history books, and, of course, Wikipedia — is that famed Nintendo game designer Gunpei Yokoi was traveling on a bullet train and noticed a bored businessman playing around with the buttons on his LCD calculator. That sparked the idea of a small device that could tell time and pass the time with a little game.

The timing of the release of the first Game & Watch in 1980, which came after Mattel’s tremendous success with handheld LCD games, and even the Microvision release made the anecdote suspect in my mind.

And according to an interview with Satoru Okada, a former general manager at Nintendo’s Research and Engineering, that’s not really what happened.

Okada says that while it’s true that Yokoi wanted to create a toy when he saw someone on a train messing around with a calculator, the real thing that gave birth to the Game & Watch was Milton Bradley’s Microvision.

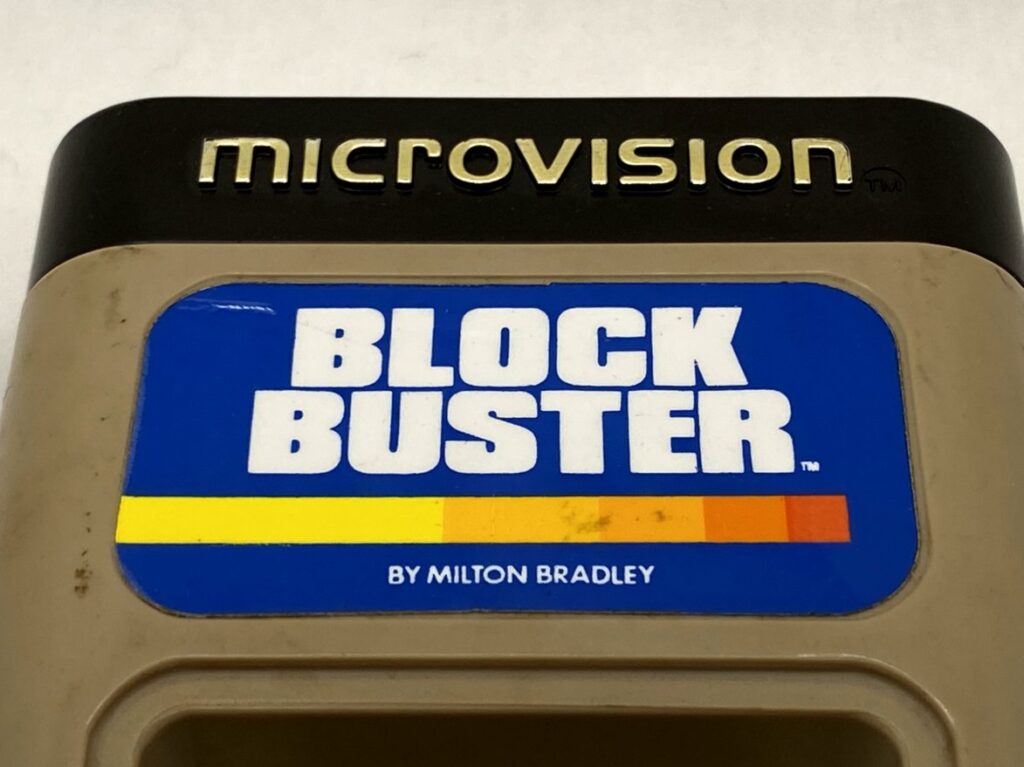

In an interview with Retro Gamer, he said, “I loved this machine and played the Breakout clone a lot. But we did not understand why the machine had to be so big! So, we first tried to make a portable console that people could really carry in their pockets, Except that the screen resolution was very poor and the graphics were very abstract. Besides, we also thought that the idea of interchangeable cartridges was interesting, but because of the Microvision’s limitations, all the cartridges looked the same, both with their graphics and the concept of the games. So we said to ourselves: ‘Why not have just one game per machine but with good graphics at least.’ And this is when the idea of using a calculator screen became self-evident. All of this led to the birth of the Game & Watch. Yokoi would design the games, and l was in charge of the technical part, the electronics even and coding the games.”

That makes a lot more sense.

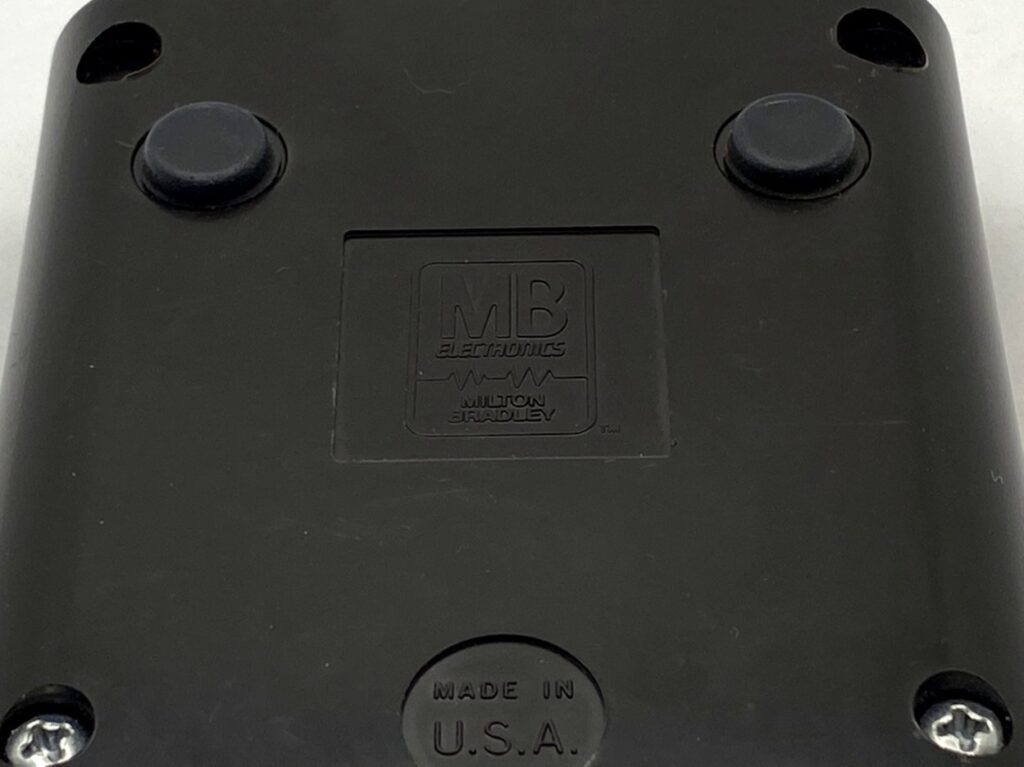

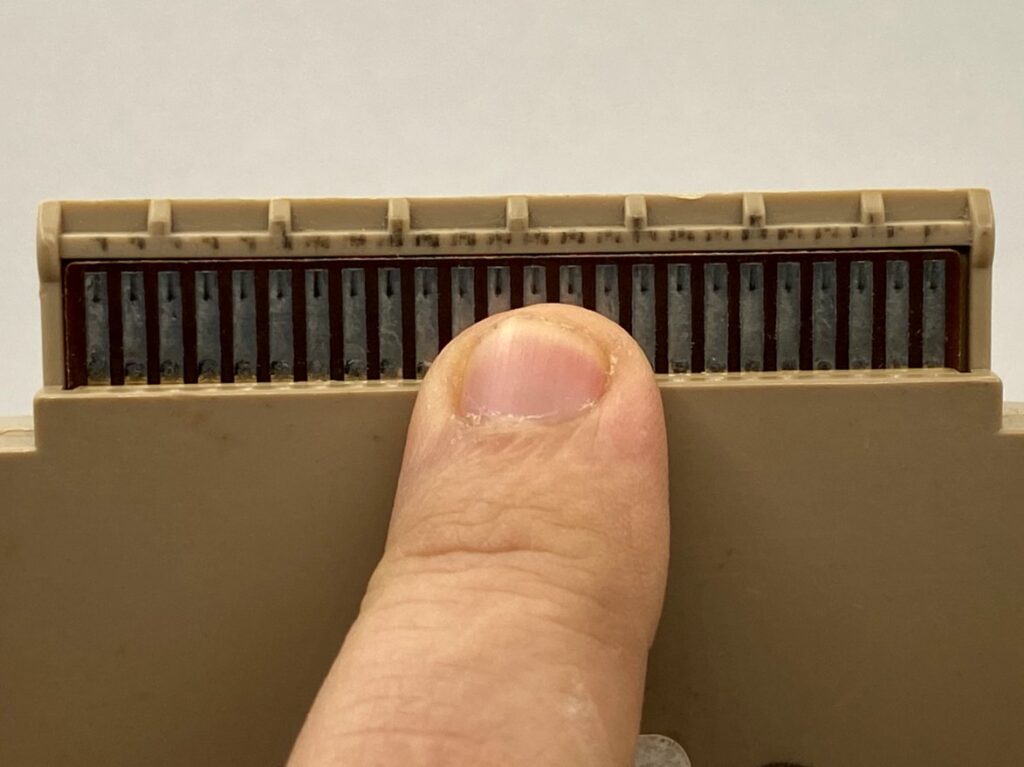

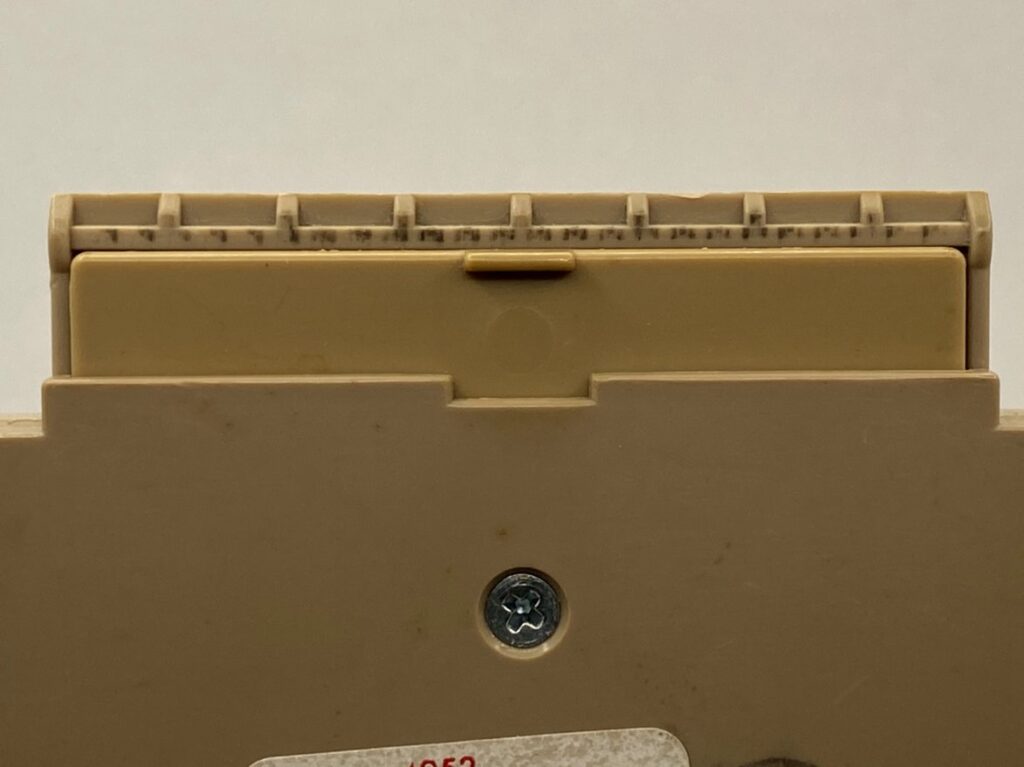

The Microvision, which launched in November 1979, was the first successful gaming handheld to include the ability to swap out games using a sort of cartridge. In this regard, the system was a bit unusual. The base unit didn’t have an onboard processor. Instead, each game included its own processor. So the base unit basically consisted of an LCD screen, the port for slotting in the game, a dial controller, and a thick pad, under which a 12-button keypad was hidden. The cartridge would slide into the slot at the top of the system and snap at the bottom — just above that dial — with cut-outs for whichever of the 12 buttons were going to be used for that game. The cut-outs each had a thin film over them with words printed on them to tell you what the bottom did. The name of the game was printed on a big label above the LCD cut out.

The system comes in two versions. The initial version required two 9-volt batteries to support the original Intel 8021 cartridge processors. The system was then switched over to games that ran on the Texas Instruments TMS1100 processors, which only required a single 9-volt battery. But, to work around the need to change the production mold for the system, the new systems still have space for two batteries, but only terminals for one. The second spot is called a “battery holder” in the new system and isn’t required to play games.

The system sold for $50 a pop and was a massive hit for developer Smith Engineering. The company grossed $15 million in the first year alone.

But a number of issues lead to its relatively quick demise. That included a slew of technical issues born of what seemed to be poor quality control as well as a lack of support from third-party developers and marketing by Milton Bradley.

Ultimately, the system only had a dozen games released for it, and finding a working system today can be a challenge.

In an interview with the Retro Gaming RoundUp podcast, Jay Smith, the engineer who designed the Microvision and later the Vectrex gaming console, said the handheld was inspired by the desire to make better use of LCDs. That was because Smith Engineering was involved in creating the LCD chemicals that went into the displays. The key to the handheld was a secret new system that allowed Smith Engineering to produce a much larger 16-by-16 LCD.

Smith said they came up with the display first and then figured out how they could use it in a gaming system. The next idea was making it a cartridge system, so they could keep reusing that amazing (for the time) display. It was cheaper to use a very inexpensive microprocessor in each cartridge than to build a processor in the system, so they went with that approach.

They also were told by Milton Bradley to double the size of the system so that it would seem like it was worth the price tag. Had they gone with the original system, it would have been about the size of a Game Boy.

Smith Engineering pitched both a 32-by-32 display and color display Microvision, but Milton Bradley passed, noting that they already released a Microvision and didn’t see any sense in coming out with a follow-up, according to Smith on the podcast.

Smith also noted the games that were available for the system all seemed reminiscent of Milton Bradley’s board games and not as original as they could have been.

The resulting system, though, is an interesting piece of gaming history and one that apparently inspired Nintendo to get into handheld gaming.

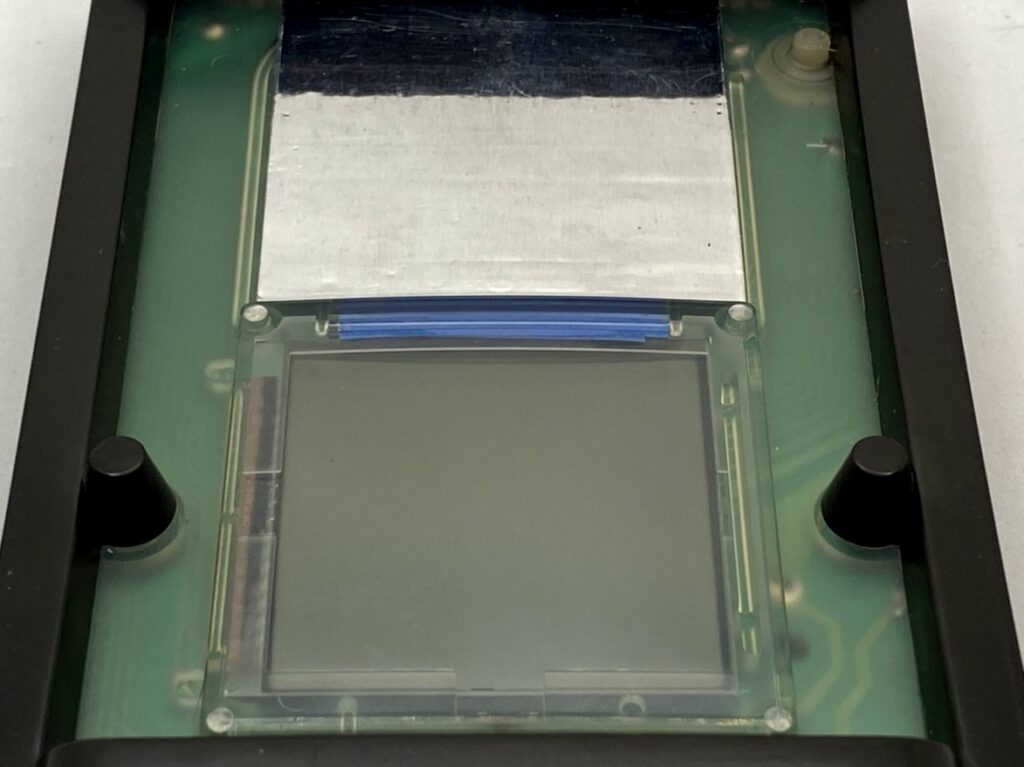

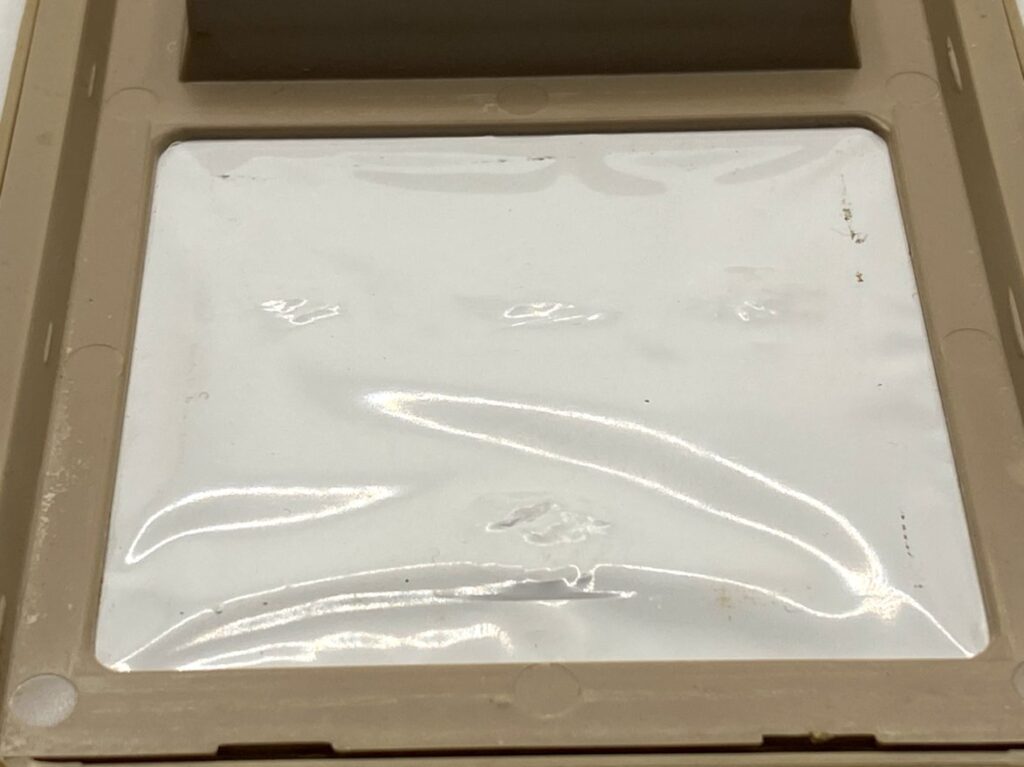

If you’re interested in picking up one of these systems today, chances are you will find a Microvision suffering from one of three issues: screen rot, electrostatic damage, or a broken keypad. It’s worth checking all of these before you plunk down the cash.

The good news is that not only is there a vibrant community of Microvision collectors and fans out there willing to help with self-repairs, there are also people who will replace things like the LCD for you for a relatively small fee.\

I had a new LCD soldered into my system for about $40 ($30 for the screen and $10 for the labor), and it works great.

There’s not a lot of diversity in the game selection, but it’s an interesting and impactful handheld that I’m happy I have in my collection.

Love retro handhelds? Well then, have I got a bunch of stories, videos, and pictures for you.